If one street in America can claim to be the most infamous, it is surely 42nd Street. Between Seventh and Eighth Avenues, 42nd Street was once known for its peep shows, street corner hustlers and movie houses. Over the last two decades the notion of safety-from safe sex and safe neighborhoods, to safe cities and safe relationships-has overcome 42nd Street, giving rise to a Disney store, a children's theater, and large, neon-lit cafes. 42nd Street has, in effect, become a family tourist attraction for visitors from Berlin, Tokyo, Westchester, and New Jersey's suburbs.

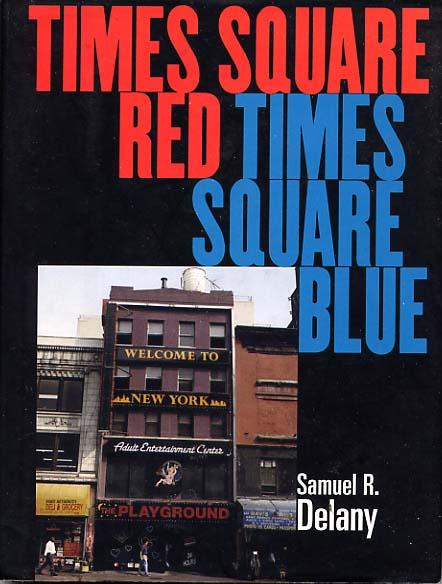

Samuel R. Delany sees a disappearance not only of the old Times Square, but of the complex social relationships that developed there: the points of contact between people of different classes and races in a public space. In Times Square Red, Times Square Blue, Delany tackles the question of why public restrooms, peepshows, and tree-filled parks are necessary to a city's physical and psychological landscape. He argues that starting in 1985, New York City criminalized peep shows and sex movie houses to clear the way for the rebuilding of Times Square. Delany's critique reveals how Times Square is being "renovated" behind the scrim of public safety while the stage is occupied by gentrification.

Times Square Red, Times Square Blue paints a portrait of a society dismantling the institutions that promote communication between classes, and disguising its fears of cross-class contact as "family values." Unless we overcome our fears and claim our "community of contact," it is a picture that will be replayed in cities across America.

Quotes and thoughts while reading:

This has to be one of the more interesting books I've read. The first half was incredibly erotic and raunchy. Althought raunchy isn't really the word that I'm looking for. It was graphic, yes, that's the word. Graphic. I've never before sat in a room full of people and read something akin to this. On top of that, the second half is incredibly powerful - with the first half serving as ample referential situations on contact vs. networking. I was shocked at Delaney's second thesis, and am excited to revisit those pages. Let's jump in.

"The (strictly heterosexual) pornographic movies started as a Saturday offering. At first management was afraid the straight films might drive away the theatres gay audience. The tickets' color coding allowed them to compare the take from days when sex films played, and days when legit films ran. The figures for the porn were pretty good, however. Soon it was pornographic Tuesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays, with legit films the other days. Within a year and a half, it was double-feature porn Monday through Saturday. On Sunday, in deference to what I'll never know, a porn film alternated with a legit offering. That persisted for another year, till the porn drove out even that."(p 19) I've never been to a porn theatre - and doubt many exist any more. And I have to reflect on how fascinating it is that there was this swing towards pornography. What does it say about our culture on a larger level? Given the opportunity and social acceptability are we all horn dogs? Voyeurs? Or is that just one of the ways we identify and when an outlet is present we take it?

"Back then - in '75 or '76 - the Metropolitan and a number of the theatres in the Forty-second Street area were being fed a stream of all but amateur work. Appearing in film after film, the main actor was an avuncular guy in his late thirties. His screen persona was friendly enough and soft-spoken. Certainly he was not ugly. But her was a little dumpy, and he was distinctly bald. No one would have looked at him twice on the street.... By the eighties a whole new stable of actors had taken over the city's pornography screens. They were younger. Many of them, now, were traditionally prettier..." (p 31) Just the use of the word avuncular cracked me up in that section. But there is an incredibly insightful comment on the next page.

"I don't see any reason that a woman (or women) couldn't take on any (or every) role I've already described or will go on to describe for any (and every) male theatre patron. That includes the guy joking with his cousin, and his cousin's friends, coming down the stairs, genitals exposed - though it does unmitigated violence to the West's traditional concept of "women". But I believe it is only by inflicting such violences on concept that we can prevent actual violence against women's bodies and minds in the political, material world."(p 32) Do you realize what he is saying? Read it again. And read it again. He's talking about a woman flashing her genitals, and how in our western culture that would be seen as "un-ladylike". Let's chew on that. And then read the next part - that by only inflicting that imagery on the minds of others can women break free from actual harm and violence placed upon them in this patriarchal society. Isn't the very concept of "ladylike" violence on the psyche of women? Enforcing a behaviour that is completely concepted and not based in any real, logical, truth? When Delany can follow something up like avuncular porn stars, with insight like this, the power of this book comes to fruition.

"But sitting in the Capri, talking with his cut dick out, he explained. "I love to come, man. I mean I love to come more than anything in the world. And I like people to see men come. I like them to know I'm coming. I like the to hear me come. I like them to love it that I'm coming, too!" (p 45) My note card says - "How do I talk about this book" - but then looking further down the page I see this wisdom from Delany: "There are as many different styles, intensities, and timbres to sex as there are people The variety of nuance blends into the variety of techniques and actions employed, which finally segues, as seamlessly, into the variety of sexual objects the range of humankind desires. Certainly one of the necessary places where socializing and sexualizing actually touch for, dare I call it, health or just contentment..." (p 45) Again - this book will surprise you, from the top of the page to the bottom.

"The skin on most cocks, no matter how much of a workout they get, is pretty soft. But his, head to hair, was thick, leathery, dry, like the skin on the ball of your foot. I gripped it tighter and began to rub... I couldn't believe he'd actually gone to sleep with someone jerking on his small, rocky dick... My hand was becoming tired, so I stopped. Within seconds, his own hand crawled over his lap to grasp himself. As he started pumping, his eyes opened and, like someone waking on the couch... he blinked and lifted his head. "How much time... How long did I sleep?" (p 70 - 71) Joe was a chronic masturbator, with a serious mental illness. And it's in this contact, in this brief moment that Delany interacts with this guy - that is where the core of the book lies. It's in those spaces where you wouldn't normally find yourself, that you can learn something about someone, and yourself.

"Generally, I suspect, pornography improved our vision of sex all over the country, making it friendlier, more relaxed, and more playful - qualities of sex that, till then, had been often reserved to a distressingly limited section of the better-read and more imaginative members of the middle classes." (p 78) It's fascinating to write/read this in contrast to "The End of Protest" which talks about pornography as a terror on society. It makes me want to send this book to Micah...

"Once, when WAP (Women Against Pornography) was leading its tours through the area in the early eighties, I did an informal tabulation of six random

commercial porn films in the Forty-second Street area and six random legit movies playing around the corner in the same area during the same week. I counted the

number of major female characters portrayed as having a profession in each: the six legit films racked up seven (one had three, one had zero). The six porn films

racked up eleven. On the same films I took tabs on how many friendships between women were represented, lesbian or otherwise, in the plot. The six legit films came

out with zero; the six porn films came out with nine. Also: How many of each ended up with the women getting what they wanted? Five for the porn. Two for the legit." (p 70) Hmm - so what's that say about media and representation of women?

"The primary thesis underlying my several arguments here is that, given the mode of capitalism under which we live, life is at its most rewarding, productive, and pleasant when large numbers of people understand, appreciate, and seek out interclass contact and communication conducted in a mode of good will."(p 111) Boom - the book takes an astoundingly different tone. And from this point on - we use this thesis - but reference back to the atmosphere presented in the first half. This notion of "contact" has been on my mind a lot lately. Let's sink into it further.

"I have written of how a shift in postal discourse may be signed by the rhetorical shift between “she would not receive his letters” and “she would not open his letter.” What intervened here was the 1840 introduction of the postage stamp, which changed letter writing from an art and entertainment paid for by the receiver to a form of vanity publishing paid for by the sender. (There was no junk mail before 1840.)" (p 118) This how section on rhetorical changes is fascinating. "The shift from landlord visits to superintendents in charge of repairs is signaled by the rhetorical shift between “the landlord saw to the repairs” as a literal statement and “the landlord saw to the repairs” as a metaphor. I say “shifts,” but these rhetorical pairings are much better looked at, on the level of discourse, as rhetorical collisions. The sign that a discursive collision has occurred is that the former meaning has been forgotten and the careless reader, not alert to the

details of the changed social context, reads the older rhetorical figure as if it were the newer." (p 119) While I find the bit about the "post" fascinating - as to the introduction of the stamp. I think the more illuminating thing is to how the introduction of new structures and institutions can change language. And how we can track society based on these changes.

"Given the mode of capitalism under which we live, life is at its most rewarding, productive, and pleasant when large numbers of people understand, appreciate, and seek out interclass contact and communication conducted in a mode of good will.

The class war raging constantly and often silently in the comparatively stabilized societies of the developed world perpetually works for the erosion of the social practices through which interclass communication takes place and of the institutions holding those practices stable, so that new institutions must always be

conceived and set in place to take over the jobs of those that are battered again and again till they are destroyed.

While the establishment and utilization of those institutions always involve social practices, the effects of my primary and secondary theses are regularly perceived at the level of discourse. Therefore, it is only by a constant renovation of the concept of discourse that society can maintain the most conscientious and informed field for both the establishment of such institutions and practices and, by extension, the necessary critique of those institutions and practices—a critique necessary if new institutions of any efficacy are to be established. At this level, in its largely stabilizing/destabilizing role, superstructure (and superstructure at its most oppositional)can impinge on infrastructure." (p 121) Whew - this is why I feel a calling to support institutions that make "contact" possible. This book has brought to light how the structure we live in is actively attempting to distance us from each other.

"I have taken “contact,” both term and concept, from Jane Jacobs’s instructive 1961 study, The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Jacobs describes contact as

a fundamentally urban phenomenon and finds it necessary for everything from neighborhood safety to a general sense of social well-being. She sees it supported by a strong sense of private and public in a field of socioeconomic diversity that mixes living spaces with a variety of commercial spaces, which in turn must provide a variety of human services if contact is to function in a pleasant and rewarding manner... Astute as her analysis is, Jacobs still confuses contact with community. Urban contact is often at its most spectacularly beneficial when it occurs between members of different communities. That is why I maintain that interclass contact is even more important than intraclass contact." (p 126-127)

"There is, of course, another way to meet people. It is called networking. Networking is what people have to do when those with like interests live too far apart

to be thrown together in public spaces through chance and propinquity. Networking is what people in small towns have to do to establish any complex cultural life

today.

But contemporary networking is notably different from contact.

At first one is tempted to set contact and networking in opposition. Networking tends to be professional and motive-driven. Contact tends to be more broadly social and appears random. Networking crosses class lines only in the most vigilant manner. Contact regularly crosses class lines in those public spaces in which interclass encounters are at their most frequent. Networking is heavily dependent on institutions to promote the necessary propinquity (gyms, parties, twelve-step programs, conferences, reading groups, singing groups, social gatherings, workshops, tourist groups, and classes), where those with the requisite social skills can maneuver. Contact is associated with public space and the architecture and commerce that depend on and promote it. Thus contact is often an outdoor sport; networking tends to occur indoors.

The opposition between contact and networking may be provisionally useful for locating those elements between the two that do, indeed, contrast. But we must

not let that opposition sediment onto some absolute, transcendent, or ontological level that it cannot command. If we do, we will simply be constructing another opposition that we cannot work with at any analytical level of sophistication until it has been deconstructed—a project to which we shall return.

The benefits of networking are real and can look—especially from the outside—quite glamorous. But I believe that, today, such benefits are fundamentally misunderstood. More and more people are depending on networking to provide benefits that are far more likely to occur in contact situations, and that networking is specifically prevented from providing for a variety of reasons." (p 129)

"Recently when I outlined the differences between contact and networking to a friend, he came back with the following examples: “Contact is Jimmy Stewart; networking is Tom Cruise. Contact is complex carbohydrates; networking is simple sugar. Contact is Zen; networking is Scientology. Contact can effect changes at the infrastructural level; networking effects changes at the superstructural level.” (p 141)

"Infrastructure makes society go. Superstructure makes society go smoothly (or bumpily)." (p 162)

"The approach to planning I propose flies in the face of both these assumptions as principles—with the result that, at least to

most people at first, it may look like no planning at all.

Today our zoning practices are overwhelmingly exclusionary. They function entirely to keep different kinds of people, different kinds of business, different kinds of income levels and social practices from intermingling.

I suggest that we start putting together policies that mandate, rather, a sane and wholesome level of diversity in as many urban venues as possible." (p 167) This is literally the exact thing Brian was talking about on New Years' Eve! And he's right. And so is Delany. Our rural area that has been zoned suburban needs to diversify everything. The people, the type of business, residential mixed with business. That's what drives contact!

"If our ideal is to promote movement among the classes and the opportunity for such movement, we can do it only if we create greater propinquity among the

different elements that make up the different classes.

That is diversity.

Today, however, diversity has to claw its way into our neighborhoods as an afterthought—often as much as a decade after the places have been built and

thought out. (It is not just that there were once trees and public ashtrays on Forty-second Street between Seventh and Eighth Avenues. There were also an apartment

house and grocery stores, an automat, a sporting goods store, clothing stores, bookstores, electronics stores, a cigar store and several newsstands, and half a dozen restaurants at various levels, all within a handful of meters of the Candler office tower—as well as the dozen movie theaters and amusement halls [Fascination, Herbert’s Flea Circus], massage parlors and sex shows for which the area was famous, for almost fifty years—fifty years that encompassed the heyday and height of the strip as the film and entertainment capital of the city, of the world.) Why not begin by designing for such variety?

At the human level, such planned diversity promotes—as it stabilizes the quality of life and the long-term viability of the social space—human contact." (p 179)

"“Why is there homophobia?” and “What makes us gay?”

As I listened to the discussion over the next hour and a half, I found myself troubled: Rather than attack both questions head-on, both discussants tended to

veer away from them, as if those questions were somehow logically congruent to the two great philosophical conundrums, ontological and epistemological, that

ground Western philosophy—“Why is there something rather than nothing?” and “How can we know it?”—and, as such, could be approached only by elaborate in-

direction.

It seems to me (and this will bring the multiple arguments of this lengthy discussion to a close under the rubric of my third thesis: the mechanics of discourse)

that there are pointed answers to be given to the questions “Why is there homophobia?” and “What makes us gay?”—answers that are imperative if gay and lesbian men and women are to make any progress in passing from what Urvashi Vaid has called, so tellingly, “virtual equality” (the appearance of equality with few or none of the material benefits) to a material and legal-based equality." (p 184)

"The question “What makes us gay?” has at least three different levels on which answers can be posed.

First, the question “What makes us gay?” might be interpreted to mean “What do we do, what qualities do we possess, that signal the fact that we partake

of the preexisting essence of ‘gayness’ that gives us our gay ‘identity’ and that, in most folks’ minds, means that we belong to the category of ‘those who are gay?’”This is, finally, the semiotic or epistemological level: How do we—or other people—know we are gay?

There is a second level, however, on which the question “What makes us gay?” might be interpreted: “What forces or conditions in the world take the potentially ‘normal’ and ‘ordinary’ person—a child, a fetus, the egg and sperm before they even conjoin as a zygote—and ‘pervert’ them (i.e., turn them away) from that ‘normal’ condition so that now we have someone who does some or many or all of the things we call gay—or at least wants to, or feels compelled to, even if she or he would rather not?” This is, finally, the ontological level: What makes these odd, statistically unusual, but ever-present gay people exist in the first place?" (p 187) I always find it useful to have examples of ontological vs epistemological questions. This whole section - on how you are even asking the question in fascinating - and where Delany shows himself as the linguist and teacher. it's the power of "sociolinguistics" and what it means to use phases like "to make, to produce, to create".

"Following directly from my primary thesis, my primary conclusion is that, while still respecting the private/public demarcations (I do not believe that property is theft), we’d best try cutting the world up in different ways socially and rearranging it so that we may benefit from the resultant social relationships. For decades the governing cry of our cities has been “Never speak to strangers.” I propose that in a democratic city it is imperative that we speak to strangers, live next to them, and learn how to relate to them on many levels, from the political to the sexual. City venues must be designed to allow these multiple interactions to occur easily, with a minimum of danger, comfortably, and conveniently. This is what politics—the way of living in the polis, in the city—is about."(p 193)

"The freedom to “be” “gay” without the freedom to choose to partake of these institutions is just as meaningless as the freedom to “be” “Jewish” when, say, any given Jewish ritual, text, or cultural practice is outlawed; it is as meaningless as the “freedom” to “be” “black” in a world where black music, literature, culture, language, foods, and churches and all the social practices that have been generated through the process of black historical exclusion were suddenly suppressed. I say this not because a sexual preference is in any necessary way identical to a race, or for that matter identical to a religion. (Nor am I proposing the equally absurd notion that a race and a religion are equivalent.) I say it rather because none of the three—race, religion, or sexual preference—represents some absolute essentialist state; I say it because all three are complex social constructs, and thus do not come into being without their attendant constructed institutions.

Tolerance—not assimilation—is the democratic litmus test for social equality." (p 194)

<< click to go back

© JKloor Books