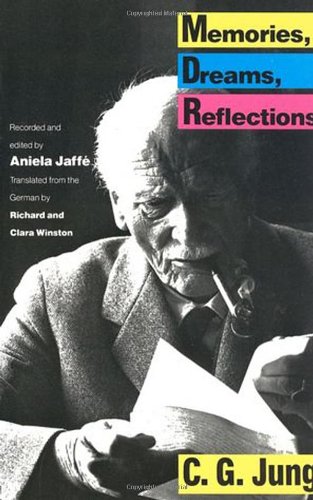

In the spring of 1957, when he was eighty-one years old, C. G. Jung undertook the telling of his life story. At regular

intervals he had conversations with his colleague and friend Aniela Jaffe, and collaborated with her in the preparation

of the text based on these talks. On occasion, he was moved to write entire chapters of the book in his own hand, and he

continued to work on the final stages of the manuscript until shortly before his death on June 6, 1961.

This edition of Memories, Dreams, Reflections includes Jung's VII Sermones ad Mortuous. It is a fully corrected edition.

Quotes and thoughts while reading:

This comes up time and time again, but I thought it was so interesting that Jung has such vivid memories and thoughts from

another century, going so far as to write 1786 instead of 1886. He has these two personalities, No. 1, and No. 2. The

interplay between the two as he ages continues to be of note.

"Clinical diagnoses are important, since they give the doctor a certain orientation; but they do not help the patient.

The crucial thing is the story. For it alone shows the human background and the human suffering, and only at that point

can the doctor's therapy begin to operate. " (p 124)

In reaction to a local mystic this part was particularly poignant:

"The Indian's goal is not moral perfection, but the condition of nirdvandva. He wishes to free himself from nature;

in keeping with this aim, he seeks in meditation the condition of imagelessness and emptiness. I, on the other hand,

wish to persist in the state of lively contemplation of nature and of the psychic images. I want to be freed neither

from human beings, nor from myself, nor from nature; for all these appear to me the greatest of miracles. Nature, the

psyche, and life appear to me like divinity unfolded--and what more could I wish for? To me the supreme meaning of Being

can consist only in the fact that it is, not that it is not or is no longer." (p 276)

"Nevertheless it may be that for sufficient reasons a man feels he must set out on his own feet along the road to wider realms.

It may be that in all the garbs, shapes, forms, modes, and manners of life offered to him he does not find what is peculiarly

necessary for him. He will go alone and be his own company. He will serve as his own group, consisting of a variety of opinions

and tendencies--which need not necessarily be marching in the same direction. In fact, he will be at odds with himself, and will

find great difficulty in uniting his own multiplicity for purposes of common action. Even if he is outwardly protected by social

forms of the intermediary stage, he will have no defense against his inner multiplicity. The disunion within himself may cause him

to give up, to lapse into identity with his surroundings.

Like the initiate of a secret society who has broken free from the undifferentiated collectivity, the individual on his lonely

path needs a secret which for various reasons he may not or cannot reveal. Such a secret reinforces him in the isolation of his

individual aims. A great many individuals cannot bear this isolation. They are neurotics, who necessarily play hide-and-seek with

others as well as with themselves, without being able to take the game really seriously. As a rule they end by surrendering their

individual goal to their craving for collective conformity-- a procedure which all the opinions, beliefs, and ideals of their

environment encourage..." (p 343)

© JKloor 2015 Books