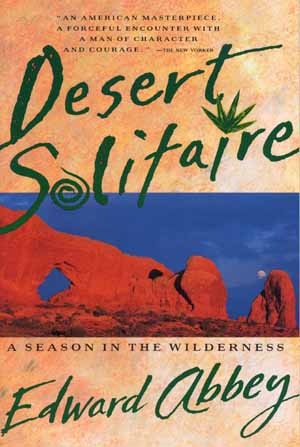

When Desert Solitaire was first published in 1968, it became the focus of a nationwide cult. Rude and sensitive. Thought-provoking and mystical. Angry and loving. Both Abbey and this book are all of these and more. Here, the legendary author of The Monkey Wrench Gang, Abbey's Road and many other critically acclaimed books vividly captures the essence of his life during three seasons as a park ranger in southeastern Utah. This is a rare view of a quest to experience nature in its purest form -- the silence, the struggle, the overwhelming beauty. But this is also the gripping, anguished cry of a man of character who challenges the growing exploitation of the wilderness by oil and mining interests, as well as by the tourist industry.

Abbey's observations and challenges remain as relevant now as the day he wrote them. Today, Desert Solitaire asks if any of our incalculable natural treasures can be saved before the bulldozers strike again.

Quotes and thoughts while reading:

Abbey writes beautifully the disconnect that technology causes us from nature. A flashlight "tends to separate man from the world around him. If I switch it on my eyes adapt to it and I can only see the small pool of light which it makes in front of me; I am isolated. Leaving the flashlight in my pocket where it belongs, I remain a part of the environment I walk through and my vision though limited has no sharp boundary." (p 13) Abbey also expounds on living in his housetrailer, and how when he turns on the generator at night, to supply him with light he is "shut off from the natural world and sealed up, encapsulated, in a box of artificial light and tyrannical noise." (p 13) Abbey talks at length about the visitors/tourists and how they keep themselves trapped in their little automobiles, unwilling to step outside them and explore the natural beauty around them. We "exchange a great and unbounded world for a small, comparatively meager one", which affords us comforts, but is severely limited.

Abbey wants more than anything else to keep the wild wild, and the point of closing off national parks to automobiles surfaces multiple times. "The motorized tourists, reluctant to give up the old ways, will complain that they can't see enough without their automobiles to bear them swiftly(traffic permitting) through the parks. But this is nonsense. A man on foot, on horseback or on a bicycle will see more, feel more, enjoy more in one mile that the motorized tourist can in a hundred miles. Better to idle through one park in two weeks than try to race through a dozen in the same amount of time." (p 54)

"At once I spot the unmistakable sign of tourist culture - tin cans and tinfoil dumped in a fireplace, a dirty sock dangling from a bush, a worn-out tennis shoe in the bottom of a clear spring, gum wrappers, cigarette butts, and bottlecaps everywhere. This must be it, the way to Rainbow Bridge; it appears that we may have come too late. Slobvious americanus has been here first." (p 190) Here's one thing that bothers me a little bit, Abbey is no saint, and in previous works I've read he's written that he's tossed a can into a lake, rolled a tire into the Grand Canyon, so on and so forth. And I see that it is the viewpoint I have to find the fault in people's statements, and his sentiment is valuable - pack out what you packed in - but the hypocrisy makes it such that when Abbey says it, I roll my eyes a bit. The name, however, Slobvious americanus is very good, and I will certainly reference it in the future.

It's important to note, Abbey the explorer and lone wilderness trekker, almost gets himself killed, and tells the story in this book (it's in the Havasu chapter). It's nice to romanticize the wilderness, to strike out upon the great trails that surround us alone and to commune with nature, and it's also important to remember that it can be deadly. I'm happy that Abbey included this, that he made it out alive, and that he showed us how one simple choice, to strike down a canyon in pursuit of a new way back to camp, can cause us to weep in the face of death, and only by the slimmest of margins "emerge from that treacherous little canyon" (p 205).

"The plow of mortality drives through the stubble, turns over rocks and sod and weeds to cover the old, the worn-out, the husks, shells, empty seedpods and sapless roots, clearing the field for the next crop. A ruthless, brutal process - but clean and beautiful.

A part of our nature rebels a part of our nature rebels against this truth and against that other part which would accept it. A second truth of equal weight contradicts the first, proclaiming through art, religion, philosophy, science and even war that human life, in some way not easily definable, is significant and unique and supreme beyond all the limits of reason an nature. And this second truth we can deny only at the cost of denying our humanity." (p 214)

"... I discovered that I was not opposed to mankind but only to mancenteredness, anthropocentricity, the opinion that the world exists solely for the sake of man; not to science, which means simply knowledge, but to science misapplied, to the worship of technique and technology, and to that perversion of science properly called scientism; and not to civilization but to culture." (p 244) Abbey continues to expound on this subject, and the whole section is worth a read. He explains in detail the difference between culture and civilization, "Civilization is the vital force in human history; culture is that inert mass of institutions and organization which accumulate around and tend to drag down the advance of life..."(p 246), but that is just a small sample of the examples given. I agree with Abbey, mancenteredness only goes to show our hubris and ego, two forces that will destroy our world(or at least drastically change it from it's current form), and to destroy ourselves.

I've appreciated the viewpoint Abbey has given me over the last month or so. I wouldn't recommend Desert Solitaire as one's first Abbey book, but it's a good one. Abbey died at 62 years of age, wow. It's also probably true that he lived more during those 62 years than most do in 90. I like the lens Abbey saw the world through, he brought a sense of nature back into my life, and impressed upon me that man is more than his technology and science that surrounds him. He can turn off his flashlights and generators, and though his vision may be limited, it won't have any kind of sharp boundary.

© JKloor 2016 Books