Medicine has triumphed in modern times, transforming birth, injury, and infectious disease from harrowing to manageable. But in the inevitable condition of aging and death, the goals of medicine seem too frequently to run counter to the interest of the human spirit. Nursing homes, preoccupied with safety, pin patients into railed beds and wheelchairs. Hospitals isolate the dying, checking for vital signs long after the goals of cure have become moot. Doctors, committed to extending life, continue to carry out devastating procedures that in the end extend suffering.

Gawande, a practicing surgeon, addresses his profession's ultimate limitation, arguing that quality of life is the desired goal for patients and families. Gawande offers examples of freer, more socially fulfilling models for assisting the infirm and dependent elderly, and he explores the varieties of hospice care to demonstrate that a person's last weeks or months may be rich and dignified.

Full of eye-opening research and riveting storytelling, Being Mortal asserts that medicine can comfort and enhance our experience even to the end, providing not only a good life but also a good end.

Quotes and thoughts while reading:

This book was hard to read, at multiple times my eyes were wetted, and images of my father, thin, gaunt looking, shuffling around his tiny mobile home, with a sense of confusion and fuzzyness that seemed to permeate from him. This image came to me so many times while reading this book, and still, I'm not sure what to think of it. In any case, if you have ever lost someone, or seen someone near their death and had to make hard decision, this book will yank chords in you which you probably thought had already snapped and been cast off. Gawande has a lot to say, lets dive in.

A topic that is touched on often is how much to treat someone, and when to realize that the options you have are actually more likely to put you in a more debilitated state, rather than giving you a miraculous cure. People bet on the slimmest of margins that it almost isn't a surprise when things like this happen: Here we was in the hospital, partially paralyzed from a cancer that had spread throughout his body. The chances that he could return to anything like the life he had even a few weeks earlier were zero. But admitting this and helping him cope with it seemed beyond us. We offered no acknowledgment or comfort or guidance. We just had another treatment he could undergo. Maybe something good would result. (loc 93) And this happens so often, as we will see as the book continues. It is almost sickening to see how health care providers and patients are seemingly willing to bet it all at a cure, rather then attempting to enjoy the last few weeks, months, etc with their family.

There are also quite a few sections which remind me of my Gramma Mary in her current state, and at the same time are a grim reminder of the road she is headed towards. This is the point of the book, we are all mortal, there will be a point in our lives when we can no longer do all the things our independent selves could do. This passage in particular reminds me of my Gramma Mary, and also my Great Aunt Mary - She went to the gym with her friend Polly. She liked to sew and knit and made clothes, scarves, and elaborate red-and-green Christmas stockings for everyone in the family, complete with a button-nosed Santa and their names across the top. She organized a group that took an annual subscription to attend performances at the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. She drove a big V8 Chrevolet Impala, sitting on a cushion to see over the dashboard. She ran errands, visited family, gave friends rides, and delivered meals-on-wheels for those with more frailties than herself. (loc 176) Man, isn't that Gramma Mary to a t?

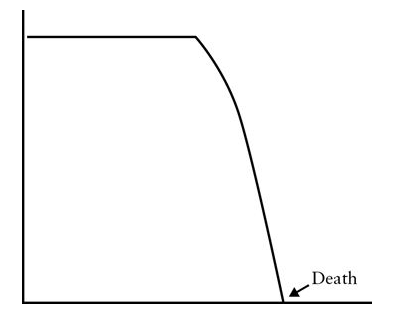

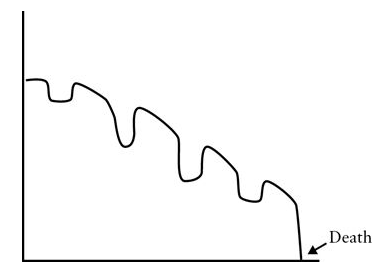

I thought it was interesting to note the change in how our lives seem to work themselves out now with these two graphs. The one on the left is how it used to be, the one on the right, what it is like now. I think it of course begs more analysis, and you can't take it at face value without any labels on the axis, but as a talking point, a place to begin the discussion I like them.

|

|

Gawande claims that the average lifespan used to be thirty years or less(loc 418), and while this makes sense, I've read quite a few articles that state that it was possible for people to live to old age, and that the average was so low because people at the time practiced infanticide. Whether or not Gawande is correct, it is most certainly true that people can be sustained with diseases for much longer than thought possible 100 years ago. It is also worth mentioning that Gawande quoted Montaigne, a philosopher I still need to read.

'The problem [of choking while eating] is common in the elderly. Listen.' I realized that I could hear someone in the dining room choking on his food every minute or so. (loc 679)

I was reminded of Doug and Phyllis often as well. It is striking, how hearing the common stories of the elderly can bring up thoughts regarding those you know and love. People who you thought were unique in their predicament, are actually working through a common issue. That issue is when one person in the relationship grows older, faster, than the other person. [Felix] had no medical crises and maintained his weekly exercise regimen. He continued to teach chaplaincy students geriatrics and to serve on Orchard Cove's health committee. He didn't even had to stop driving. But Bella was fading. She lost her vision completely. Her hearing became poor. Her memory became markedly impaired...(loc 729) It's a common occurrence, but it feels so different to read about when you know an elderly couple going through the same issues.

There is a sense of fragility when you are an elderly couple that is perfectly expressed here: One day, however, they had an experience that revealed just how fragile their life had become. Bella developed a cold, causing fluid to accumulate in her ears. An eardrum ruptured. And with that she became totally deaf. That was all it took to sever the thread between them. With her blindness and memory problems, the hearing loss made it impossible for Felix to achieve any kind of communication with her...(loc 741) I know Doug and Phyllis have this very fear, that someday they won't be able to communicate with one another, and I worry what will happen then. This is, to me, one of the scariest parts of growing older, how in the blink of an eye, your whole world can change.

The sociologist Erving Goffman noted the likeness between prisons and nursing homes half a century ago in his book Asylums. They were, along with military training camps, orphanages, and mental hospitals, 'total institutions' - places largely cut off from wider society. (loc 967) And we know, America has no issue with putting people in prisons, whether they be elderly or not. We've just come up with a better name for it - nursing home.

At the center of Wilson’s work was an attempt to solve a deceptively simple puzzle: what makes life worth living when we are old and frail and unable to care for ourselves? In 1943, the psychologist Abraham Maslow published his hugely influential paper “A Theory of Human Motivation,” which famously described people as having a hierarchy of needs. It is often depicted as a pyramid. At the bottom are our basic needs—the essentials of physiological survival (such as food, water, and air) and of safety (such as law, order, and stability). Up one level are the need for love and for belonging. Above that is our desire for growth—the opportunity to attain personal goals, to master knowledge and skills, and to be recognized and rewarded for our achievements. Finally, at the top is the desire for what Maslow termed “self-actualization”—self-fulfillment through pursuit of moral ideals and creativity for their own sake... (loc 1214) Nursing homes only satisfy this base level of life, and while the base of the pyramid is important, its not a pyramid without the parts between the base and cap, and this is true of life. It's not really life without all the levels combined.

our elderly are left with a controlled and supervised institutional existence, a medically designed answer to unfixable problems, a life designed to be safe but empty of anything they care about. (loc 1436)

In 1908, A Harvard philosopher named Josiah Royce wrote a book with the title The Philosophy of Loyalty. Royce was not concerned with the trials of aging. But he was concerned with a puzzle that is fundamental to anyone contemplating his or her mortality. Royce wanted to understand why simply existing—why being merely housed and fed and safe and alive—seems empty and meaningless to us. What more is it that we need in order to feel that life is worthwhile?

The answer, he believed, is that we all seek a cause beyond ourselves. This was, to him, an intrinsic human need. The cause could be large (family, country, principle) or small (a building project, the care of a pet). The important thing was that, in ascribing value to the cause and seeing it as worth making sacrifices for, we give our lives meaning...

The only way death is not meaningless is to see yourself as part of something greater: a family, a community, a society. If you don’t, mortality is only a horror. But if you do, it is not. Loyalty, said Royce, 'solves the paradox of our ordinary existence by showing us outside of ourselves the cause which is to be served, and inside of ourselves the will which delights to do this service, and which is not thwarted but enriched and expressed in such service.' (loc 1646) Woof, let's keep that in the back pocket for future reference and reflection.

An interesting question that is posed to Gawande was "Is she dying?" (loc 2064) and I found it fascinating how the answer to this question has become ambiguous, vague, and not necessarily answerable. We can keep people alive for months, years even past their bodily expiration date. So, what does that mean. Is the person dying? Or is our capacity to keep them alive destroying that question?

In ordinary medicine, the goal is to extend life. We’ll sacrifice the quality of your existence now—by performing surgery, providing chemotherapy, putting you in intensive care—for the chance of gaining time later. Hospice deploys nurses, doctors, chaplains, and social workers to help people with a fatal illness have the fullest possible lives right now—much as nursing home reformers deploy staff to help people with severe disabilities. In terminal illness that means focusing on objectives like freedom from pain and discomfort, or maintaining mental awareness for as long as feasible, or getting out with family once in a while... (loc 2109) And here is where my understanding of hospice started to blossom. I had no real inkling of what hospice was, and with this passage in particular, as well as the following chapters hospice seems to be a better option.

Gould wrote that Of course I agree with the preacher of Ecclesiastes that there is a time to love and a time to die—and when my skein runs out I hope to face the end calmly and in my own way. For most situations, however, I prefer the more martial view that death is the ultimate enemy—and I find nothing reproachable in those who rage mightily against the dying of the light. (loc 2255) I've read, and seen people rage against the dying of the light, and I think in the past I would have fallen into that category, but I'm not so sure anymore. I think, slowly, I'm coming more to grips with my mortality, and I think it comes from living a fulfilling life, a life where I take chances, and don't dread the missed opportunities. And that is a refreshing feeling to have.

The trouble is that we’ve built our medical system and culture around the long tail. We’ve created a multitrillion-dollar edifice for dispensing the medical equivalent of lottery tickets—and have only the rudiments of a system to prepare patients for the near certainty that those tickets will not win. Hope is not a plan, but hope is our plan. (loc 2262)

A landmark 2010 study from the Massachusetts General Hospital had even more startling findings. The researchers randomly assigned 151 patients with stage IV lung cancer, like Sara’s, to one of two possible approaches to treatment. Half received usual oncology care. The other half received usual oncology care plus parallel visits with a palliative care specialist. These are specialists in preventing and relieving the suffering of patients, and to see one, no determination of whether they are dying or not is required. If a person has serious, complex illness, palliative specialists are happy to help. The ones in the study discussed with the patients their goals and priorities for if and when their condition worsened. The result: those who saw a palliative care specialist stopped chemotherapy sooner, entered hospice far earlier, experienced less suffering at the end of their lives—and they lived 25 percent longer. In other words, our decision making in medicine has failed so spectacularly that we have reached the point of actively inflicting harm on patients rather than confronting the subject of mortality. If end-of-life discussions were an experimental drug, the FDA would approve it. (loc 2343)

Block has a list of questions that she aims to cover with sick patients in the time before decisions have to be made: What do they understand their prognosis to be, what are their concerns about what lies ahead, what kinds of trade-offs are they willing to make, how do they want to spend their time if their health worsens, who do they want to make decisions if they can’t? (loc 2414) These are questions I need to remember, and questions I wish someone had asked my father near his end. I think the correct choice was made in that matter, just not enough knowledge was shared.

Note to self: read Plato's dialogue, the Laches on courage.

I think, in closing, I'm going to touch on a topic that came up again and again, and that is one of time. Often, as referenced by Gawande, the families, and people who are terminal, are thinking in time scales of years, while the reality of the situation is really something like weeks or months. Enough time to get your affairs in order, but not enough to continue living your life as it was. The problem stems from medical professionals, who are too hopeful with their patients, or not forthright enough to share all the details of the situation. Gawande himself remarks in reflection that he has told patients again and again that the risk of the surgery is worth it, as they could get back to their life. I think this is the great shame of the medical community currently. I understand instilling hope, but if the chances are incredibly slim, I don't believe that it's right for a Doctor to present your chances in any manner less than an analogy to the lottery. I suppose, in this regard, there is a bitterness and regret that this sort of mindset and reality wasn't presented to my father and his family in regards to his final days. He believed he had years after his surgery, that he would be able to go back to work, and engage in normal activities. I knew this wasn't the case, and I was only 18, his heart was decreased to 25% capacity, you don't go back to work with 1/4 of a heart. But he didn't know, He wasn't told. He was told, all would be fine, because the Doctors and Surgeons didn't know how to have the very difficult conversation of letting someone know that they are on their way out. Their light is dimming.

I hope there is a sea change happening, where medical professionals are learning how to have these hard conversations, and people are coming more to grips with their mortality, and reality. Chances are slim, but thanks to reading this, my world view is in a bit of a flux, and I'm interested to see where it settles. Only time will tell.

© JKloor 2015 Books