“Murakami is like a magician who explains what he’s doing as he performs the trick and still makes you believe he has supernatural powers . . . But while anyone can tell a story that resembles a dream, it's the rare artist, like this one, who can make us feel that we are dreaming it ourselves.” —The New York Times Book Review

The year is 1984 and the city is Tokyo.

A young woman named Aomame follows a taxi driver’s enigmatic suggestion and begins to notice puzzling discrepancies in the world around her. She has entered, she realizes, a parallel existence, which she calls 1Q84 —“Q is for ‘question mark.’ A world that bears a question.” Meanwhile, an aspiring writer named Tengo takes on a suspect ghostwriting project. He becomes so wrapped up with the work and its unusual author that, soon, his previously placid life begins to come unraveled.

As Aomame’s and Tengo’s narratives converge over the course of this single year, we learn of the profound and tangled connections that bind them ever closer: a beautiful, dyslexic teenage girl with a unique vision; a mysterious religious cult that instigated a shoot-out with the metropolitan police; a reclusive, wealthy dowager who runs a shelter for abused women; a hideously ugly private investigator; a mild-mannered yet ruthlessly efficient bodyguard; and a peculiarly insistent television-fee collector.

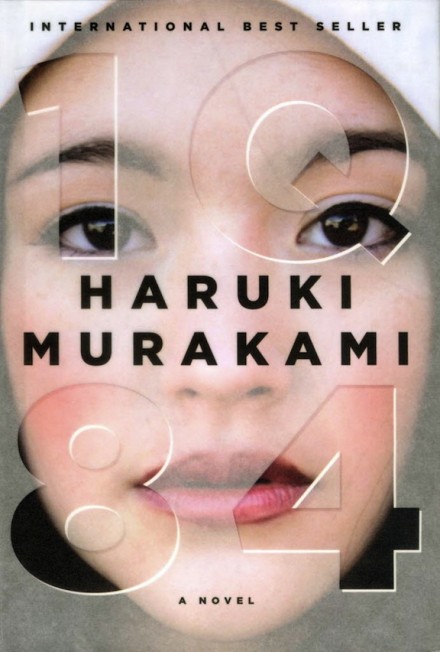

A love story, a mystery, a fantasy, a novel of self-discovery, a dystopia to rival George Orwell’s—1Q84 is Haruki Murakami’s most ambitious undertaking yet: an instant best seller in his native Japan, and a tremendous feat of imagination from one of our most revered contemporary writers.

Quotes and thoughts while reading:

There is something magical about how Murakami can capture my attention so fully. He can envelope me in a world as if I am wrapped in a baby blanket. This one especially, possibly because Tengo is both a mathematician and writer, but also because it seems like Murakami writes for people who love to read, and for people who love to write(I'm not sure those two groups are the same). Kafka on the Shore was an amazing introduction to Murakami, and The Wind Up Bird Chronicles was a fascinating world to crawl into, but 1Q84 took me so much further than either of those two books.

There are times when it seems Murakami is speaking directly to the reader, through conversations between characters. "Komatsu raised the hand that had a cigarette tucked between the fingers. 'Think of it this way, Tengo. Your readers have seen the sky with one moon it any number of times, right? But I doubt they've seen a sky with two moons in it side by side. When you introduce things that most readers have never seen before into a piece of fiction, you have to describe them with as much precision and in as much detail as possible. What you can eliminate from fiction is the description of things that most readers have not seen.' " (p 173)

Books that were mentioned in 1Q84 that I need to look into further:

The Tale of the Heike

Tales of Time Now Past

Sansho the Bailiff

The music in Murakami's books plays a huge role. He is always citing some piece, or setting the mood with a song playing in the background. Something I had never run into before was the concept of BMV numbers (p 206). I had to look it up: There are over 1000 known compositions by Johann Sebastian Bach. Nearly all of them are listed in the Bach-Werke-Verzeichnis (BWV), which is the best known and most widely used catalogue of Bach's compositions. Janacek's Sinfonietta opens the book, and is referenced many many times. When reading, I always think, "I should put on whatever music Murakami is trying to make me hear as I read this." But I never seem to.

Murakami writes some pretty erotic scenes, they've been in all the book I've read so far. And the one between Fuka-Eri and Tengo was incredible to read. It's not stated in the passage below, but Fuka-Eri is around 17 or 18(from reading it now without context she sounds very young, which I'm sure is intentional.) It's also interesting, how after this erotic scene, Tengo still doesn't look upon Fuka-Eri sexually. This was a pivotal scene in the story, that caused a progression, and yet while it involved sex, it wasn't really sex, it was just intercourse as Tengo says later.

" 'Don't worry,' Fuka-Eri said, moving her body lower down on his. The meaning of her movement was clear. Her eyes had taken on a certain gleam, the hue of which he had never seen before.

It seemed inconceivable that his adult penis could penetrate her small, newly formed vagina. It was too big and too hard. The pain should have been enormous. Before he knew it, though, every bit of him was insider of her. There had been no resistance whatever. The look on her face remained totally unchanged as she brought him inside. Her breathing became slightly agitated, and the rhythm with which her breasts rose and fell changed subtly for five or six seconds, but that was all. Everything seemed like normal, natural part of everyday life." (p 479) It goes on, and it would be worth it to write down here, but reading what follows without everything else would be silly. The world pivoted upon this union, and the story changed subtly.

"Earlier ways of finding information - going to the National Diet Library, sitting at a desk with piles of bound, small-sized editions of old newspapers, or almanacs - might soon become a thing of the past. The world might be reduced to a battlefield, the smell of blood everywhere, where computer managers and hackers fought it out. No, "the smell of blood" isn't accurate, Ushikawa decided. It was a war, so there was bound to be some bloodshed. But there wouldn't be any smell. What a weird world. Ushikawa preferred a world where smells and pain still existed, even if the smells and pain were unendurable. Still, people like Ushikawa might become out-of-date relics." (p 662)

This weird thing happened on page 780, where the narrator's voice suddenly changed, so much so that I was thrown out of the book, and questioned "Did the voice change? No, it didn't... wait, hmm, it did though." Those are my notes for that page, it was very strange. And it was shocking how fully it pulled me out of the book.

My father died the first weekend of February in 2009, and while I forget sometimes the precise day it happened, I find myself reading the right thing magically around this time of year. Tengo loses his father, whom he was not close to in any way. And from that Tengo is told this: "Your father may have had a secret that he took with him to the other side. And that seems to be causing you confusion. I think I can understand how you feel. But you shouldn't peep anymore into that dark entrance. Leave that up to cats. if you keep doing so, you will never go anywhere. Better to think about the future." (p 861) I don't believe in cosmic forces, but when I was talking to my sister later, and she reminded me of our fathers passing, I flashed back to this scene.

Murakami has a talent for ending books. For a long period of time I was frustrated with every ending of every book I'd read for a couple month's straight. Kafka on the Shore broke that streak, and Murakami continues to delight with the endings. They don't usually feel rushed to end, and they don't always end happily for the sake of happiness, they end as I think the characters deserved them to end. 1Q84 is a near 1000 page book, and was immensely fun to read. Murakami took his time letting us, the reader, get to know his characters, and it was wonderful to have that chance. More Murakami is in my future, I'm just not sure what yet.

© JKloor 2016 Books